This article first appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of Homestead Living magazine.

Whether you are a backyard hobbyist or a full scale homesteader, my guess is that you have at least flirted with the idea of raising your own meat chickens. Perhaps you are still in the dreaming stage, or maybe you have already filled your freezer a time or two. Regardless, I bet you have looked at a Cornish Cross, gone through the logistics of shipping and timing, and thought, “I want to do this by myself.”

I hear the same complaints and comments all the time. “I’m just tired of having to rely on someone else. The hatchery never has them when I want them. Why can’t I just breed my own?” And, on one hand, I get it. I understand the desire to raise your own sustainable meat flock. In many ways, chickens symbolize freedom. Freedom from running to the grocery store on a Sunday morning when you’ve run out of eggs. Freedom to grab a chicken or two from the freezer for a special roast dinner. Freedom from relying on others to put food on your table when you want it.

But…I’m going to try to be as nice as I can with this one. The truth is: you can’t raise your own sustainable flock of Cornish Cross chickens, because you can’t breed them on your own. That can be really hard to hear, especially for those of us who have made it our life’s work to figure out how to do hard things for ourselves.

The truth of it is that in order to reproduce the most popular meat bird in North America, you would have to raise and care for thousands and thousands of chickens that you would never even think about eating. You’d have to spend your time planning out new breeding coops, evaluating and selecting parent stock, and you’d keep more records on your chickens than you could possibly imagine. Though many of us wish for the end result to be readily at our fingertips and in our backyards, we can’t always have our cake and eat it, too, folks. Most people don’t have the space, time, or long-term ability to start their own Cornish Cross breeding program from the ground up.

There is no way for the average person to replicate the meaty, broad-breasted bird that dominates as the most consumed meat in the country as you are used to it. And for the record, there are no genomic CRISPR-gene-editing mutant chickens responsible for the most common food source in the world. Cornish Cross are not a Franken-chicken lab experiment gone wrong. They are the result of generations upon generations of selectively breeding lines and parent stock.

Commercialization in the Meat Industry

So what does this mean for us backyard homesteaders and working farmers, those of us who want to put dinner on the table for our families? Well … you know your family tree? Chickens have those, too. Instead of your Grandpa picking out your Grandma from all the other gals because she was the best dancer at the county fair, these chickens are selected for putting on weight as fast as possible.

In 1951, 60% of broiler breeders in the US were crosses of a Cornish (duh, Cornish Cross) and a New Hampshire. They weren’t white yet, they were actually red. This was the first market shift from dual purpose birds to strictly broiler breeding. With the rise in popularity of grocery stores, which is a story for a different time, people were no longer raising their own meat and eggs. This allowed for an industry solely dedicated to the specialization of meat chickens. Big corporations flocked to be a part of this new opportunity, and have controlled the breeding lines ever since. These major corporations at the top of the industry have about a 60 year head start on your passion for creating a Cornish Cross type breeding program.

Extreme Chicken Math

It takes a hen to get an egg, and it takes an egg to get a chick. In the case of commercial broilers, it actually takes about 14 hens and 14 roosters (at least) to get a broiler. And for an extra layer of complication, only one sex is used from each specific line to produce the next generation. So, at best, half of the birds in each line are unusable within any given breeding program. For each broiler you dream of hatching at home and raising to butcher, you would have to raise 14-20 chicks to perpetuate each line, plus some for crossing for the next generation. The math gets pretty daunting when you talk about just how many birds are needed to avoid massive inbreeding within each line.

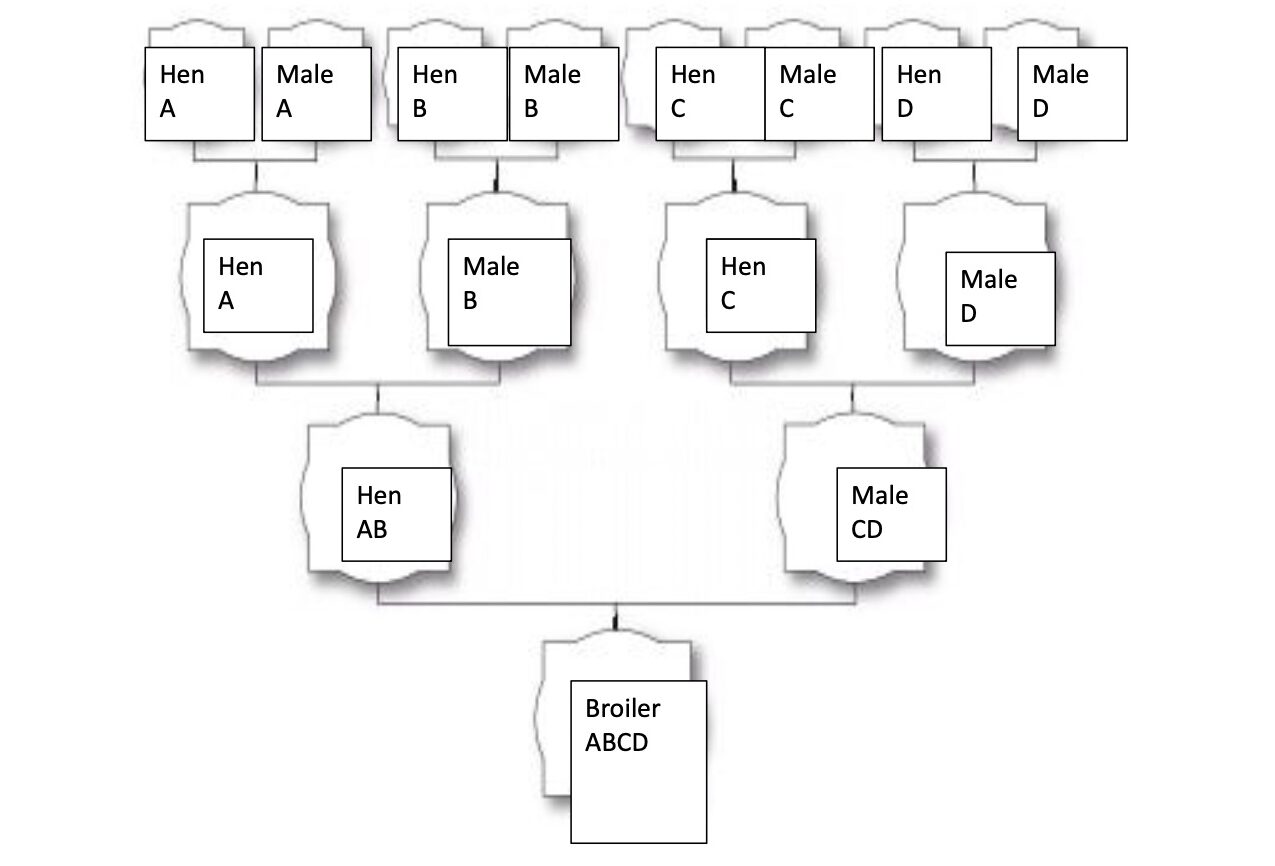

What does any of this have to do with why you can’t reproduce these particular broilers on your farm? You can absolutely raise your very own (delicious) sustainable meat flock, but only if you temper your expectations. At the end of the day, the Cornish broiler is a four way cross between eight breeding lines that are all heavily selected for growth rate. If you only want to replicate that grocery store slab of 10oz breast meat, don’t read any more. Cut your losses here, enjoy the fun fact that broilers used to be red, and order some Cornish Cross chicks to raise up for your table. There’s no shame in it, and many of us still choose to do it that way.

A Simple Solution

What can we do to keep a full freezer, knowing that we can’t start our own Cornish Cross breeding program? The answer is very simple when you think about it. Do what your grandparents and great grandparents and great great grandparents did before commercialization defined every priority. You need to selectively raise a dual purpose flock that provides both meat and eggs. No, you won’t get chicken breasts that you have to split in half to cook. Again, temper your expectations. The tradeoff is creating a program that is better for you, the birds, and the environment. If you are determined, a sustainable meat flock that meets your family or community’s needs for delicious chicken tendies and Sunday roast spreads requires nothing but a little time and a lot of bookkeeping.

Start with good Heritage stock. Do what they did in 1951. Select two different breeds for different things. You’ve got your Cornish for breast size and easy plucking. There is a reason they used Cornish breeds back then and still do now. They have, by far, the largest proportion of breast meat to any other breed. And their beautiful, tight feathers pluck well. We sell both Dark and White Laced Red Cornish, which are sure to help you throw some rotund gals into the mix. Then, pick a large bird to pump up your lines. New Hampshires, Delawares, and Rhode Island Reds all have really nice rooster size. Now, let those two breeds dance to create some hybrid vigor, and you’re on your way to raising your own sustainable meat flock.

Record Keeping

All breeders need to keep records, more than you might imagine. With cows and pigs, it might be a notebook. With chickens, you are going to need spreadsheets. So, so much data is involved in breeding chickens. The more you have, though, the more successful you are going to be in the long run. Records need to be kept by individual chick. No, I am not joking. I would never joke about chicken keeping records.

Records for each individual chick:

- Weight at 1 week

- Weight at 3 weeks

- Weight at 6 weeks

- Weight at 16 weeks (whoa…we are way off broiler specs here)

- Start of lay (normally 20-24-ish weeks depending on time of year)

Records for the whole flock:

- Hatchability for hens

- Fertility for roosters

- Number of eggs

Get Really Good at Building Breeding Pens

Focusing on weight is the fastest way to progress a breeding program for broilers. It’s not the only consideration, but it is Priority Number One if you want a decent meat bird on the table at the end of the day. At every weigh-in, you need to cull the birds that are smallest. That doesn’t mean you have to off them right there, unless you are particularly hungry that day. Just move the pipsqueaks to a non-breeding pen, and eat them when they are bigger. I don’t recommend keeping small hens for layers, unless you’re only adding a handful of favorites back into a separate layer coop that you already happened to have. You are going to have multiple pens for chickens throughout this endeavor, and you won’t have space to keep all the unusable breeders. Yes, you are going to need to keep multiple pens. Those strapping New Hampshires you started with? They need their own pen. Those ever-so-handsome White Laced Red Cornish you took my advice about? They need their own pen. The offspring from those two lines? You guessed it. You see where I’m going with this…you’ll need a lot of pens to house a lot of birds, so it doesn’t make a lot of sense to hang on to the ones that don’t enhance your program.

Within each breeding pen, you need at least 50 hens and 6 roosters. That is the minimum number of birds I recommend for close breeding while keeping enough genetic diversity to not cause problems for about 10-20 years. You should be selecting for weight in each of these pens when you replace these flocks. Now, switch your roosters. Put the White Laced Cornish in with the New Hampshire ladies, and vice versa. Now those eggs are producing your hybrid cross.

Then Build Some More Breeding Pens

You are going to need a pen for the offspring of those lines. The chicks from the two parent lines are going to have what is called heterosis, a fancy term for what some call hybrid vigor. This is a natural increase in size and growth rate, egg laying, and/or fertility that wasn’t present in the parent stock. This type of cross is known as an F1 cross. Two pure genetic lines mated create a hybrid. You need to keep all the same records for this group as your parent group. But here’s the tricky part. What do you do with this group? Breed them together? No, hybrids mated together don’t have the same characteristics, or pumped-up genes, that the first cross did. They don’t breed true. So, this group can be your table birds and egg layers. The increased size and growth rate of your hybrids make them a better option than either line of parent stock alone.

Let’s recap a little bit. You have two parent breed pens with 50-60 birds each, and just hatched an incubator full of their little adorable peeps. Now you have another 100 birds that are going to need a home for at least 20 weeks. This is probably a good time to ask how much chicken your family eats. Maybe we should have started with that…oh well, too late now! My family eats about 60-70 chickens a year, so that incubator could set us up nicely. You can butcher when males are roughly 16 weeks, and at about 20 weeks for females. Or, butcher the males and keep the females for egg layers until you need more nuggets. The better you are at selecting your breeders for size and growth rate, the sooner you’ll see their lines put size on, and the sooner you can butcher them. This is the whole reason you are here.

Lines A, B, C and D are pure bred lines. This might include a Cornish, a Plymouth Rock, or other non-Heritage breed. Lines can be the same breed, as long as they are genetically different.

Keep the Eggs Coming

Do you need 200 birds a year? Easy, just hatch another batch in the incubator. If you are producing for your community, you can keep that baby pumping. The most realistic way to pay to support hundreds of chickens is to have a constant output. Find a market for your birds that makes them support themselves. You’ll go broke if you try to feed this many birds just for your own consumption.

When it comes time, you are going to need to replace your parent stock. Switch your roosters back so the New Hampshires are back with the New Hampshires, and so forth. This is called pure line mode. It takes about 2 to 3 weeks for the semen to dissipate from a hen from a previous mating (a fun party fact!) Once that time has passed, you are back in business. Now, to replace a breeding flock of 50 hens and at least 6 roosters, you are going to need about 400 eggs from each pure line.

Whoa there Timmy, that’s a lot of eggs to hatch! If you set 400 eggs and have a 75% hatch rate, you are now at 300 chicks. We can assume half of those are males, so you are at 150 hen chicks. And while that may seem like a lot, the number one rule in breeding chickens is to give yourself birds to cull. You are looking to retain only the exceptional for your breeding program. Keeping 1 in 3 is actually kind of low. If it was show birds, you should be keeping 1 in 25 or 50. This part is really important. Really. If you are not culling and keeping only the best and fastest growing, you are never ever going to do more than have backyard chickens.

If all of this sounds too daunting to begin with, you can totally keep just one flock of sustainable meat chickens. I would suggest a large bodied bird that lays well, like a Delaware (I know a guy with a few good lines.) All of the record keeping still applies, no matter what scale you are working on. I suggest you keep 100 hens and at least 20 roosters in a single flock setup. This is the smallest I like to go because it keeps the inbreeding stress off a little longer, for more like 20-25 years.

My Personal Tips for Packing on the Pounds

There are a couple of tricks you can do that will help birds put weight on faster in any scenario or any breed. First, leave the lights on longer. Longer daylight hours means your birds will be eating more. Even just having a light on a timer that turns on for an hour in the middle of the night will spur them to eat. More food means more weight. The next tip is to keep your birds comfortable. No, I’m not suggesting that you air condition our chicken coop, but keeping their temperature regulated helps them grow out quicker. Less energy expenditure used to keep them warm means more weight gain. Less heat stress means they will eat more. I don’t like to eat when I’m sweating either.

And that’s it. That’s the whole deal. Keep records and cull really hard. Be relentless, select for size. Easier than calculating the half-life of radioactive isotopes.

Build Your Farm and Future

At the end of the day, you can’t have that giant broiler chicken as a sustainable homestead alternative. But when you really think about it…why would you want to? It never was sustainable, the bird or the meat industry as a whole. You are fully and completely capable of raising a sustainable meat flock that meets your family’s needs. In doing so, I think you will find that even though your birds won’t be several meals within themselves, they are better tasting, and far better for you when raised under your own attention and care. I don’t think my grandma ever cooked a chicken breast on its own. But her chicken soup was glorious, and I remember it fondly still. The chickens of the past aren’t gone. They are as persevered in time as only Heritage birds can be. It’s our expectations that have changed, and what we gave up in the name of size is both health and taste. Convenience is nice sometimes, but it should not be the standard on which we build a farm and a future.

Tom Watkins is the President and co-owner of Murray McMurray Hatchery in Webster City, Iowa. Tom and his father-in-law, Bud Wood, are building on the company’s 105 year-old legacy of hatching the highest quality baby poultry in the U.S. Tom manages day-to-day operations of the hatchery which offers more than 120 varieties of chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys, and many other types of poultry and fowl. Tom, his wife Ashley, and their four children have a 5-acre homestead in central Iowa where they raise chickens, turkeys, hogs, and Scottish Highland cattle.

Feature photo courtesy of Anna Christian. Photo of pastured meat birds courtesy of Mike Dickson, The Fit Farmer. Illustration of clan breeding courtesy of Tom Watkins.